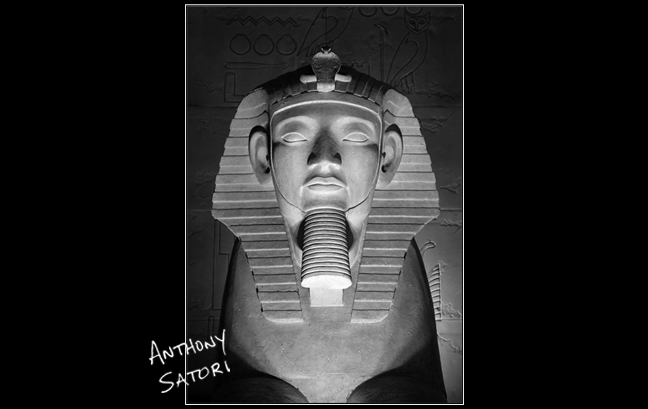

“Sphinx (with Cobra Adornment)” | Anthony Satori

A “therianthrope” is a creature or entity which is part animal, part human. In some traditions, therianthropes are even thought to be able to move between their animal and human states fluidly, thus being capable of calling upon their heightened powers at will.

“Apotheosis” is the elevation of something or someone from a secular status to the level of a god. It can also mean when an object or a person achieves the culmination of their potential.

It is surely no coincidence that we often name our brands of automobile – some of our most powerful modern tools – after animals. From Jaguar to Pantera to Mustang, we identify these intensely personal and empowering machines with the names and images of some of the most natively powerful creatures that we can conjure, and then we drive them as if they were an extension of our own human selves. While driving, we very often come to identify completely with our vehicles, and by doing so, it is almost as if we are becoming like gods, or demi-gods, experiencing an elevation of our individual powers by extension. When we join with the spirit of a powerful animal in this way, to some degree we may be experiencing, somewhere deep in our psyche, even in our subconscious mind, something resembling a truly therianthropic apotheosis.

This concept becomes especially interesting when we consider how far back in history – even pre-history – the human race has been irresistibly drawn to the idea of therianthropy. Images and stories of part human/part animal entities – most often accompanied by a considerable elevation in prowess, even the attainment of god-like status – pervades the mythology of virtually every culture on earth. From the majestic centaurs of Greek mythology, to the alluring mermaids of ancient mariners, to the bird-gods of Native American cultures, to the formidable Minotaur destroying everyone who dared venture into his Athenian labyrinth (until he was finally killed by Theseus), hybrid human/animal creatures have populated our conceptual landscape for millennia. Even in our modern age, phantasms such as vampires and werewolves – with all of their attendant superhuman abilities – follow this same pattern.

What is particularly striking, however, is the fact that therianthropic ideations date back even further than the ancient Greeks (circa 800 BC). Similar images stretch back a mind-boggling 5,000+ years to ancient Egypt, as exemplified by the god Anubis who had the body of a man and the head of a jackal, or the Sphinx which combines distinctly human features with powerful feline attributes.

Even more remarkable, therianthropic images reach even further back than this, upwards of an astounding 40,000+ years in the cave paintings of Europe. In fact, the very earliest of mankind’s visual expressions – that is, the very first subjects humans considered important enough to capture in representative artworks – portray a remarkably rich array of unmistakably therianthropic creatures, painted directly alongside entirely realistic representations of animals which lived at the time. From the very beginning, mankind has been depicting therianthropes, and such representations continue to show up, unabated, for the entirety of the thread of human artistic and mythological expression, all the way up to the present moment. It is clear that we have been dreaming of such metamorphoses – and the accompanying apotheoses – since the beginning of human imagination. Is it any wonder, then, that we would reach for such elevations in our use of modern technology? How could we not attempt to use our power of innovation to create extensions and elevations of our mortal being, when we have been imagining such hybrid existences since the beginning of time?

Or maybe – just maybe – such images were not mere figments of our imagination, at all, but were actually attempts to preserve a hazy and almost-forgotten past. Were the ancient cave painters perhaps actually depicting something real in their experience or recent memory? Does the veil of human pre-history hide a vastly more fantastic story of this planet than we could ever imagine? Did actual therianthropes roam the earth, and were these ancient depictions and mythologies actually realistic depictions of a world both fantastic and utterly familiar to these early artists and storytellers?

It is clear that deep echoes of such concepts resonate powerfully in our human minds. It is up to us to decide, then, in the face of such universality, if such ideations are purely products of our imagination, or if they are rather our collective consciousness trying to connect us with some deeper recollections of a mysterious, yet very real, past.